The Tulip Diaspora

The tulip has become a national symbol of the Netherlands, as iconic as the windmill or a pair of wooden shoes. But the tulip has won over hearts and gardens in many other nations on its journey from the mountains of Central Asia.

First Travels

The tulip began its life as a wildflower in the Pamir and Tien Shan ranges of Central Asia and the mountains of the Caucasus, which range from southern Russia to the high plains and peaks of Turkey and Iran.

Wild tulips, also called species tulips, raise their pretty blooms only a few inches above the ground in a limited palette of brilliant reds, yellows and oranges. They spread their seeds on the wind, and their bulbs by slow division.

Few people traveled to the mountainous regions first grew, but from time to time the bright little flower would catch the eye of passing traders and soldiers. They carried its seeds and bulbs to the courts of Persia and Turkey.

Persia

Tulips were cultivated in Persia as early as the 10th century, and remain a national symbol of Iran today. Their presence in the gardens of Baghdad and Isfahan is noted in literature. By the 11th century, the flower had become a motif in Omar Khayyam’s poetry, connecting the flower with ideals of feminine beauty. In Nizami Ganjavi’s 12th century romance, tulips spring from the blood of ill-fated lovers, Shirin and Farhad. The earliest surviving illustrations of tulips were discovered on tiles from the palace of Alāad-Dīn Kayqubād bin Kaykāvūs, who reigned over Persia from 1220 to 1237.

Persians venerated and celebrated the beautiful little flower, calling it “lale” a word that shares its letters with the holy name of God. In 1250, the poet Mushariffu d-din Sa’di described his ideal garden as an earthly paradise composed of many elements, including “bright, multi-colored tulips…”

Those tulips, whether they arrived as seeds or bulbs, were still low-growing wildflowers and were loved in their uncultivated form.

Germany

Botanist Conrad Gesner was the first person to describe tulips in western Europe. Gesner saw the flowers in 1559 in Augsburg, Bavaria at the garden of a man named Counsellor Herwart, who was known for his collection of rare plants. It’s unclear how Herwart got his flowers, but there are records that show tulip bulbs were sent to Europe along with bales of cloth and other goods in the mid 16th century.

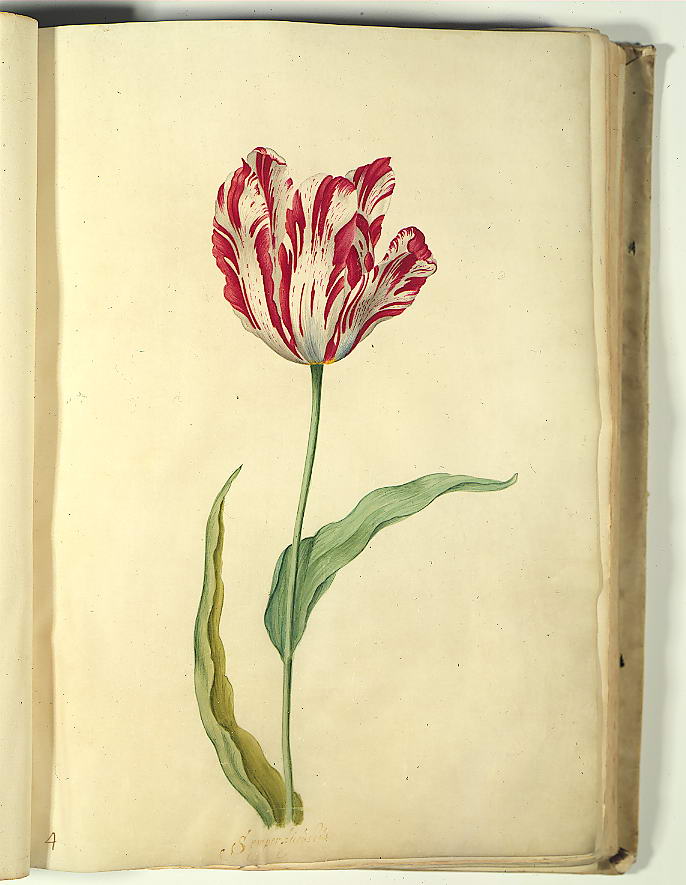

German tulip collectors had a particular passion for documenting their flowers. Leonhart Rauwolf, a physician who became a world-traveling plant scholar in the 1570s, collected striped yellow tulips along the way. He also observed the depth of Turkey’s love for the flower. Emmanuel Sweerts, an early Dutch tulip trader, published a 1612 catalog of his extensive tulip offerings called "Florilegium" in Frankfurt. Only a year later, the Bishop of Eichstatt commissioned a visual record of his garden, the "Hortus Eystettensis," spending more than 3000 florins on lavish illustrations of flowers, many of them of tulips.

France

More than 20 years before Tulipmania took hold in Holland, the French were mad for tulips. Pierre Belon, a French explorer who collected many examples of the “Lils Rouge,” a gorgeous if scentless tulip he had first described during travels in Turkey. He noted how Turkish people displayed single cut blossoms in vases and even wore tulips as items of personal adornment, remarking that many Turks tucked a flower into their turbans.

As French adoration of the flower burgeoned, a miller was said to have exchanged his mill, and thus his livelihood, for a single bulb. A groom happily accepted a striking double red and white striped tulip in lieu of any other dowry; this variety was later dubbed Mariage de ma Fille, which translates to "My Daughter's Wedding." Tulips were as expensive as fine jewels and noblewomen pinned them in their décolletage when dressing for court.

Charles de La Chesnée-Monstereul, studied tulips carefully, classifying them by bloom time, much as Carolus Clusius would in Holland, describing hundreds of varieties and noting the appealing mystery of breaking.

With time, a tulip breeding industry grew in France, led by nurserymen and florists. The flower moved from its prized place in a woman’s cleavage to strictly regimented beds in formal gardens where it stood in carefully designed ranks, the more spectacular broken tulips set to advantage among planer varieties. For a time French breeders dominated the tulip trade, but as the 18th century wore on, political upheaval and the growing importance of Dutch breeders eclipsed the French trade.